Ramaphosa's Inquiry into TRC prosecutions: A step towards justice or a PR move?

Apartheid-era crimes

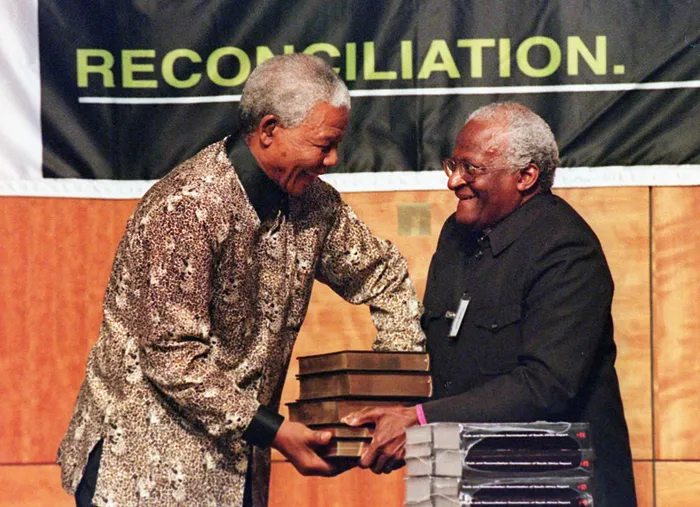

Former president Nelson Mandela receives five volumes of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's final report from Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in Pretoria on October 29, 1998. Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza's report, commissioned by the NPA, found that the NPA failed to prosecute apartheid-era crimes due to political interference between 2003 and 2017.

Image: AFP

President Cyril Ramaphosa has announced the establishment of a commission of inquiry to investigate why apartheid-era crimes, referred to by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), have not been prosecuted.

This decision follows a lawsuit filed by 25 families of victims who allege that top government officials obstructed cases referred by the TRC to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The inquiry aims to address long-standing grievances over the lack of accountability for human rights abuses during apartheid.

However, some critics argue that this move may be more of a public relations exercise than a genuine effort to deliver justice.

The ANC did not meet the 50% threshold at the 2024 national general elections, which led to the country having a Government of National Unity.

As the ANC under Ramaphosa will be contending in next year’s local government elections, the commission of inquiry is seen as more of a Public Relations exercise than a genuine inquiry.

Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza's report, commissioned by the NPA, found that the NPA failed to prosecute apartheid-era crimes due to political interference between 2003 and 2017.

Despite this, the NPA has only recently begun to investigate and prosecute these cases, with 137 cases registered for investigation and 21 matters finalised. The establishment of the inquiry has been welcomed by victims' families, but some fear it may prolong their suffering without delivering justice.

This development comes at a time when Ramaphosa is facing criticism over the government's recent decision to scrap a proposed VAT increase.

The reversal, announced after intense political pushback and intra-coalition rifts, has opened a R75 billion gap in the national budget. Critics argue that the VAT debacle has damaged the government's credibility and raised questions about its ability to govern effectively.

In this context, some view the establishment of the commission of inquiry as a strategic move to shift public attention away from the VAT controversy and demonstrate the government's commitment to justice.

However, without concrete actions and outcomes, the inquiry risks being perceived as a superficial gesture aimed at improving the government's image rather than addressing the systemic issues that have hindered the prosecution of apartheid-era crimes.

As the inquiry progresses, it will be crucial to monitor its impact on the pursuit of justice for victims of apartheid-era crimes and assess whether it leads to meaningful accountability or remains a symbolic gesture.