Rethinking social and labour plans: from compliance to transformational community development

PRESIDENTAL CLIMATE COMMISSION

Too often, when the disaster or distress hits, communities turn to mining companies to provide services and infrastructure.

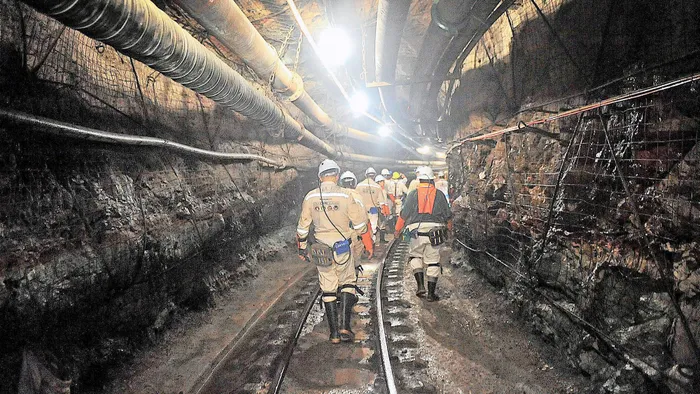

Image: Itumeleng English / Independent Newspapers.

The consequences of climate change amplify vulnerabilities in communities, placing additional stresses on water availability, agricultural productivity, health outcomes, and infrastructure resilience, such as roads and housing susceptibility to severe weather conditions.

Too often, when the disaster or distress hits, communities turn to mining companies to provide services and infrastructure.

Despite this reality, there remains a disconnect between intention, impact, and outcomes in these interventions.

Mining is on the cusp of a once-in-a-generation investment boom.

The global population is approaching 10 billion people, and many parts of the world, including us, are pursuing a net zero economy towards 2050 and beyond.

With an estimated $100 billion in additional capital investment in the resources sector required each year to meet the demand outlook associated with urbanisation and the decarbonisation of the global energy system, sizeable increases in material production and infrastructure are also necessary.

For emerging economies, there is a narrow window of opportunity to seize now.

Such growing demand brings an opportunity to benefit communities, countries and investors committed to enabling and facilitating the mining and investment activities needed to meet our needs, such as skills-to-employment ecosystem, generating local value addition and create revenue flows capable of decarbonized economic development.

South Africa’s mining sector is a significant driver of economic growth and critical for the socio-economic transformation of our society.

Central to this transformation agenda are Social and Labour Plans (SLPs), elements of the mining licensing regime which were introduced through the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act, 2002 to ensure mining contributes to sustainable community development.

SLPs were conceived as strategic tools to promote socio-economic development, stimulate and broaden economic opportunities, and enhance skills development to support the creation of sustainable communities during and after mining.

However, nearly two decades after their inception, the question remains: Have SLPs truly driven sustainable, transformative change within mining-affected communities

This ongoing struggle reveals a fundamental disconnect between the institutional understanding of challenges within communities and the intended goals and actual community-level outcomes, raising the question of why there is this persistent gap and what are the possible solutions.

Despite the significant resources mining companies have committed under SLPs, informed by local integrated development plans (IDPs), tangible and sustained improvements in the quality of life and long-term socio-economic resilience remains elusive.

A significant contributing factor is the prevailing and compliance-driven mindset underpinning SLP implementation, amongst mining companies, regulator and beneficiaries.

Too often, SLPs, being regulatory obligations, are limited from being approached as strategic investments for genuine socio-economic empowerment and, in today’s terms, transforming communities in response to climate change and commence the just transition journey.

As it stands, the law ringfences SLPs to individual mining rights, leading to less effective deployment of resources for joint projects which would deliver greater impact and minimise duplications.

Such an approach frequently leaves underlying structural challenges unaddressed.

For example, projects may initially improve conditions but deteriorate without municipal long-term planning, community stewardship, financial constraints and skills shortages to adequately sustain them.

Under such a compliance framework, companies prioritise with local government , short-term deliverables—such as building municipal and district roads, donating to local charities, a clinic here and school classroom there, or sponsoring temporary initiatives—over comprehensive, sustained, and systemic socio-economic transformation projects.

This situation ultimately limits the durability and scale of impacts, leading communities to cycle back into dependency and vulnerability. Even though, not directly affected by the SLP, lessons from the decommission of power stations, and associated mine closures in areas like Komati has brought this reality to the fore.

Recently mining companies have been trying to pool their SLP projects with amendments to legislation also being advocated.

The overarching idea is to bring the benefits of mining to communities through collaboration. But this is not often the case, as some IDPs do not exhibit the essential elements of integration along a clear developmental trajectory -resulting in sub-optimal developmental outcomes, leading to mistrust and finger-pointing.

Whereas mining companies correctly complain of the failure of government in creating an enabling environment for development, host communities often bear the brunt of such failures, including poor service delivery and ineffective local economic development.

A further complication is the apparent inadequacy of meaningful community engagement during IDP and SLP formulation.

Inadequate measurement of actual impacts exacerbates the problem. Without robust metrics to measure true progress—such as improvements in health and education outcomes or enhanced local economic development—SLPs risk remaining exercises in compliance rather than vehicles for genuine and sustained socio-economic development.

Furthermore, what is necessary to maximise this developmental impact through increased collaboration not just among mining companies within a municipality, but also with entities in other economic sectors. An appropriate legislative frameworks to guide collaboration between all economic players operating in the same mining region is urgently required.

Mining companies, together with other economic players, government, communities and other stakeholders involved can reorient SLPs away from transactional, fragmented efforts towards comprehensive, integrated, and strategic frameworks.

By doing so, SLPs can effectively contribute to the fulfilment of the developmental objective by serving as powerful catalysts for inclusive and enduring transformation in the communities that host South Africa’s critical mining operations.

Mzila I. Mthenjane is PCC Commissioner and CEO, Minerals Council South Africa.

Mzila I. Mthenjane is PCC Commissioner and CEO, Minerals Council South Africa.

Image: Supplied.

BUSINESS REPORT

Visit: www.businessreport.co.za